Lithium-Ion Battery Energy Density: How Much Energy Can We Really Store?

Introduction: Why Energy Density Is the First Question Engineers Ask

When customers approach us for a custom lithium-ion battery, the very first question is almost always the same:

“How much energy can we fit into this space — safely?”

That question is not about capacity alone. It’s about energy density, and in real-world engineering, it dictates nearly everything:

-

device size and weight

-

thermal behavior

-

cycle life

-

cost structure

-

safety margins

-

regulatory compliance

In this guide, I’ll explain lithium-ion battery energy density the way we actually use it in engineering decisions — not marketing brochures. I’ll break down the physics, materials, real limits, and the trade-offs OEM buyers need to understand before requesting a quote.

What Is Lithium-Ion Battery Energy Density?

Energy density describes how much usable energy a battery stores relative to its mass or volume.

There are two equally important definitions:

Gravimetric Energy Density (Wh/kg)

This measures energy per unit weight.

-

Formula:

Energy Density (Wh/kg) = Battery Energy (Wh) ÷ Battery Mass (kg) -

Why it matters:

Critical for portable, wearable, medical, and aerospace devices, where every gram counts.

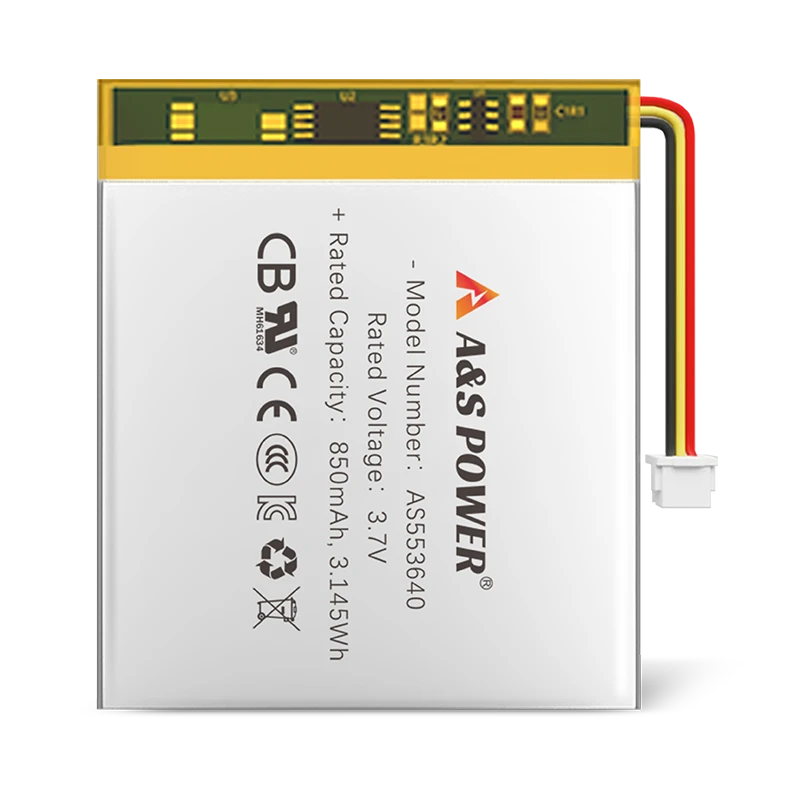

Volumetric Energy Density (Wh/L)

This measures energy per unit volume.

-

Formula:

Energy Density (Wh/L) = Battery Energy (Wh) ÷ Battery Volume (L) -

Why it matters:

Dominant factor for ultra-thin devices, compact housings, and sealed enclosures.

In real projects, we never look at only one.

The best battery is the one that balances both.

Typical Energy Density Ranges of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Based on current commercial technology (not lab prototypes), lithium-ion batteries generally fall into the following ranges:

Commercial Energy Density Benchmarks

|

Battery Type |

Gravimetric Density (Wh/kg) |

Volumetric Density (Wh/L) |

|---|---|---|

| LFP (LiFePO₄) | 140 – 180 | 300 – 350 |

| NMC (Nickel Manganese Cobalt) | 200 – 260 | 450 – 650 |

| NCA (Nickel Cobalt Aluminum) | 240 – 280 | 600 – 700 |

| Lithium Polymer (LiPo) | 180 – 260 | 500 – 700 |

| Cylindrical 21700 | 240 – 270 | 600 – 720 |

| Pouch Cell (High Density) | 260+ | 700+ |

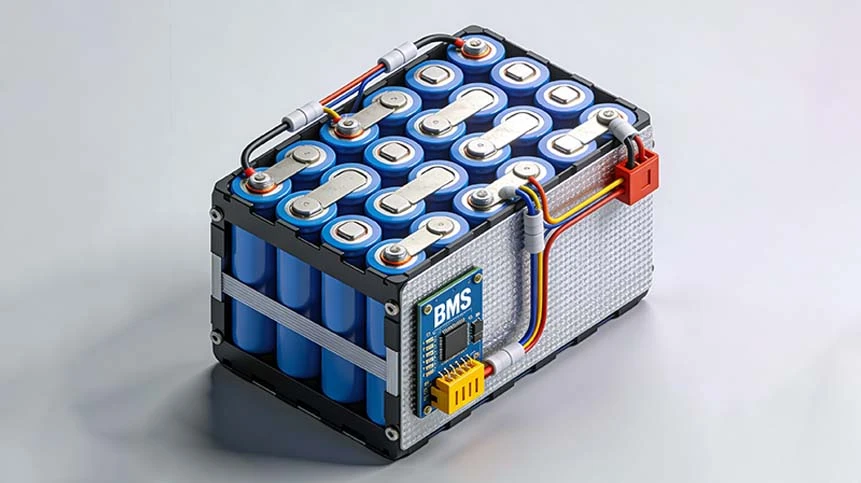

Important engineering note:

These values refer to cell-level density, not the final battery pack.

Once we add:

-

protection circuits

-

structural supports

-

thermal spacing

-

wiring and connectors

the pack-level energy density typically drops by 20–40%.

Why Energy Density Is Never “Maximized” in Real Designs

Many buyers ask us:

“Can you give us the highest energy density possible?”

From an engineering standpoint, that’s the wrong question.

The Energy Density Trade-Off Triangle

You can’t optimize all three simultaneously:

-

Maximum energy density

-

Long cycle life

-

High safety margin

Increasing energy density usually means:

-

higher nickel content

-

thinner separators

-

higher charge voltage

Which leads to:

-

faster degradation

-

tighter thermal limits

-

higher BMS requirements

Our job is not to chase numbers — it’s to deliver reliable systems.

How Battery Chemistry Impacts Energy Density

LFP vs NMC vs NCA

LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate)

-

Lower energy density

-

Extremely stable

-

Long cycle life

-

Used where safety and lifespan dominate

NMC (Nickel Manganese Cobalt)

-

Best overall balance

-

Widely used in consumer electronics, medical, and EVs

-

Flexible composition ratios (NMC 111, 622, 811)

NCA (Nickel Cobalt Aluminum)

-

Higher energy density

-

More demanding thermal management

-

Often used in EV platforms

For OEM devices, NMC remains the most common choice because it balances energy density, lifespan, and cost.

Cell Format and Its Impact on Energy Density

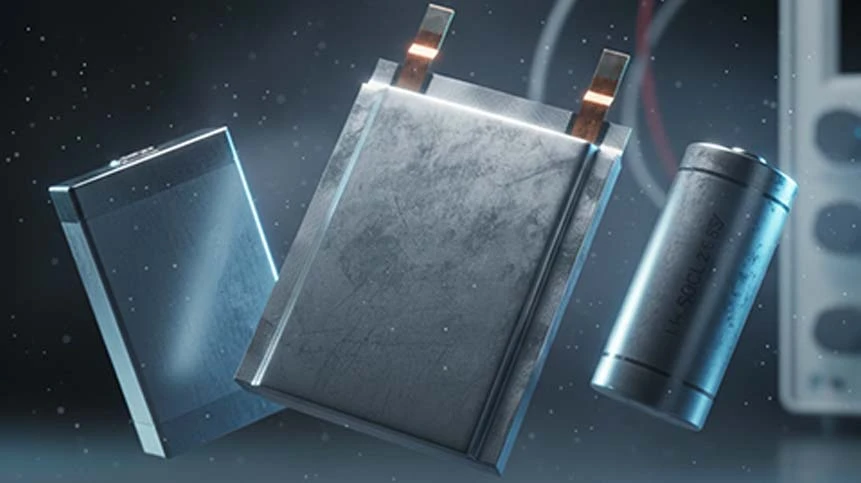

Cylindrical Cells

|

Prismatic Cells

|

Pouch Cells (LiPo)

|

For compact electronics and medical devices, pouch cells usually offer the best energy-per-volume outcome.

Energy Density vs Capacity – A Common Misunderstanding

Capacity (mAh) alone is meaningless without voltage.

Example:

-

3000 mAh at 3.7 V = 11.1 Wh

-

3000 mAh at 7.4 V = 22.2 Wh

Energy density always depends on total energy (Wh), not just capacity.

How We Evaluate Energy Density in Custom Battery Projects

When designing a custom battery pack, we evaluate:

-

Target device power consumption

-

Required runtime

-

Available volume and weight limit

-

Ambient and operating temperature

-

Expected charge cycles

-

Safety certifications required

Only then do we select:

-

cell chemistry

-

form factor

-

configuration (series/parallel)

Energy density is a design result, not a starting assumption.

Safety Limits That Cap Energy Density

There is a hard ceiling on usable energy density due to:

-

thermal runaway risk

-

electrolyte stability

-

separator thickness

-

lithium plating risk

Even though lab cells exceed 400 Wh/kg, commercial products remain far below that — by necessity, not by lack of technology.

Energy Density Trends (2024–2026 Outlook)

Based on manufacturer roadmaps and industry publications:

-

Incremental gains of 3–5% per year

-

Focus shifting toward:

-

silicon-doped anodes

-

advanced electrolytes

-

structural battery integration

-

There is no sudden breakthrough expected in mass production within the next few years.

Practical Energy Density by Application

Medical Devices

|

Wearables & IoT

|

Industrial Equipment

|

How Energy Density Impacts Cost

Higher energy density usually means:

-

higher material cost

-

stricter quality control

-

higher BMS complexity

Lowest cost ≠ highest energy density.

In many OEM projects, a moderate density design delivers better ROI.

FAQ – Lithium-Ion Battery Energy Density

What is a good energy density for lithium-ion batteries?

For commercial products, 200–260 Wh/kg is considered strong performance depending on application and safety requirements.

Can higher energy density reduce battery life?

Yes. Higher energy density often accelerates degradation if not carefully managed through BMS and thermal design.

Is lithium polymer higher in energy density than lithium-ion?

Lithium polymer is a form factor, not a chemistry. It can achieve higher volumetric energy density due to pouch packaging.

Why don’t manufacturers always use the highest density cells?

Because safety, cycle life, certification, and cost often matter more than marginal density gains.

How do I choose the right energy density for my product?

Start from device requirements, not battery specifications. A professional battery supplier should help you model this trade-off.

-

May.2026.02.27Lithium-Ion Batteries: The Six Constraints Blocking the Path to PerfectionLearn More

May.2026.02.27Lithium-Ion Batteries: The Six Constraints Blocking the Path to PerfectionLearn More -

May.2026.02.25Li-Polymer Battery 5000mAh: Complete Technical & OEM GuideLearn More

May.2026.02.25Li-Polymer Battery 5000mAh: Complete Technical & OEM GuideLearn More -

May.2026.02.24The Unparalleled Advantages of Lithium-Ion Batteries Over Traditional BatteriesLearn More

May.2026.02.24The Unparalleled Advantages of Lithium-Ion Batteries Over Traditional BatteriesLearn More -

May.2026.02.243.6 Volt Battery: Complete Technical Guide for Engineers & BuyersLearn More

May.2026.02.243.6 Volt Battery: Complete Technical Guide for Engineers & BuyersLearn More -

May.2026.02.24What Is a 3.8V LiPo Battery? A Complete Engineering & OEM GuideLearn More

May.2026.02.24What Is a 3.8V LiPo Battery? A Complete Engineering & OEM GuideLearn More